SIGN UP TO RECEIVE

15% OFF

IN YOUR NEXT TOUR

Two Extinct Galapagos Tortoise Species May Be On their Way Back to Life

SCROLL DOWN TO READ

Two Extinct Galapagos Tortoise Species May Be On their Way Back to Life

SCROLL DOWN TO READ

Two Extinct Galapagos Tortoise Species May Be On their Way Back to Life

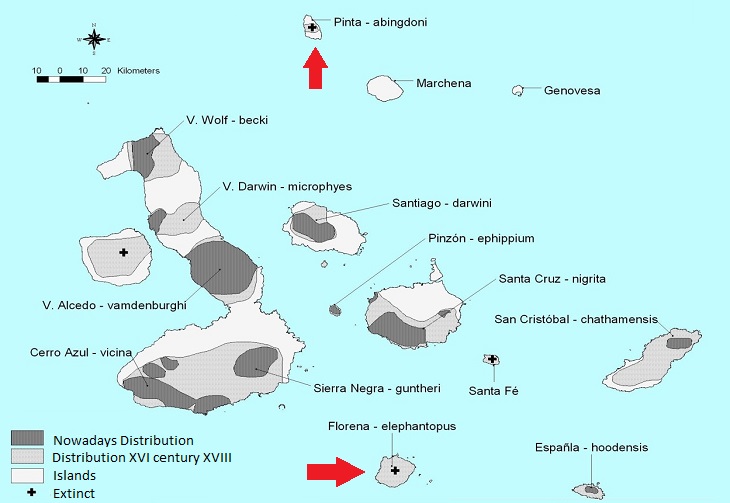

In 2012, when Lonesome George (the last living individual from Pinta Island) died the world lost another species. But now, three years after his death, scientists in Ecuador and the United States believe that they could have found a way to bring him back to life using pioneering methods to revive both the extinct Pinta Island species that George belonged to, and also restore a species from Floreana Island.

The Galápagos Islands, 620 miles (1000 KM) off the coast of South America, are probably most famous as the place that inspired Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. The archipelago is home to an extraordinary flora and fauna, including giant Galápagos tortoises, the world’s largest land-living poikilotherm animals.

In the sixteenth century, upwards of 250,000 giant tortoises are believed to have roamed the Galápagos. When Spanish explorers came upon on the islands in 1535, they actually named them for these prehistoric-looking creatures, using an old Spanish world for tortoise (galapago). Hunted down as food by pirates, whalers and buccaneers, more than 200,000 tortoises were killed over the next three centuries, and by the 1970s only 4,000 were believed to remain. Of the two primary types of tortoises (saddleback and domed carapaces) sailors preferred the smaller saddlebacks, who lived closer to the shore and were easier to catch than the domed tortoises.

Charles Darwin expounded on the harvesting of the species of tortoise found on Floreana Island, which went extinct within 15 years of his visit to the Galápagos in 1835. A similar case occurred with the tortoise found only on Pinta Island (Chelonoidis abingdoni) which became extinct in 2012, when its last individual, a male held in captivity and nicknamed Lonesome George, died. Based on the genetic identification of Lonesome George, scientists from Yale University determined that a tortoise sampled during an expedition on Wolf Volcano (in 2006) at the northern of Isabela Island was a hybrid. Incredibly, evidence was found in the DNA of that young specimen, who proved to have a pure-blooded Pinta tortoise parent who might well still be alive.

With the evidence found by scientists from Yale University, in December 2008, the Galapagos National Park organized another expedition on Wolf Volcano to search for more Pinta Island hybrids or perhaps the elusive 100% pure Pinta Island tortoise. After collecting blood samples from more than 1,600 tortoises, the scientists began the process of genetic screening of the samples. Surprisingly, they found 17 hybrid tortoises with some Pinta Island ancestry and also found 84 with partial Floreana Island tortoise ancestry. With these discoveries we have a great opportunity to restore tortoise populations on both islands.

These tortoises were collected from small and not very high islands such as Floreana and Pinta, during centuries of exploitation by whalers and buccaneers, who made the archipelago a mandatory stop-off for their crews to resupply. Old logbooks from the whaling industry indicate that, in order to lighten the burden of their ships, whalers and pirates dropped large numbers of tortoises in Banks Bay, near Volcano Wolf. Many of these tortoises made it to shore and eventually mated with the endemic Volcano Wolf species, producing hybrids that still maintain the distinctive saddleback shell found in the species from Floreana and Pinta. These hybrids include animals whose parents represent purebred individuals of the two extinct species.

The Galapagos National Park Service, following the breeding strategies recommended by scientists from Yale University, has begun a captive breeding program that would restore the genes originally found on Floreana and Pinta. The captive-born offspring of the two extinct species are expected within the next five to ten years.

However, achieving a 100% pure individual can take many years or many generations, taking into account that an average tortoise reaches its sexual maturity between 25 and 30 years, until then cloning could be a viable option.

But in the Galapagos it is not the only place where arduous restoration projects of extinct species take place. Other teams are also trying to bring different animals back from extinction through breeding. In South Africa, scientists are attempting to recreate the quagga, an extinct subspecies of the zebra, aurochs (a wild ancestor of domesticated cows), the quagga (a South African zebra), a giant flightless bird once common in New Zealand, the bush moa and the Australia's iconic carnivours marsupial, the Tasmanian tiger, might even get to roam again one day too.